“Midway this way of life we’re bound upon, I woke to find myself in a dark wood. Where the right road was wholly lost and gone.(1)”

“Midway this way of life we’re bound upon, I woke to find myself in a dark wood. Where the right road was wholly lost and gone.(1)”

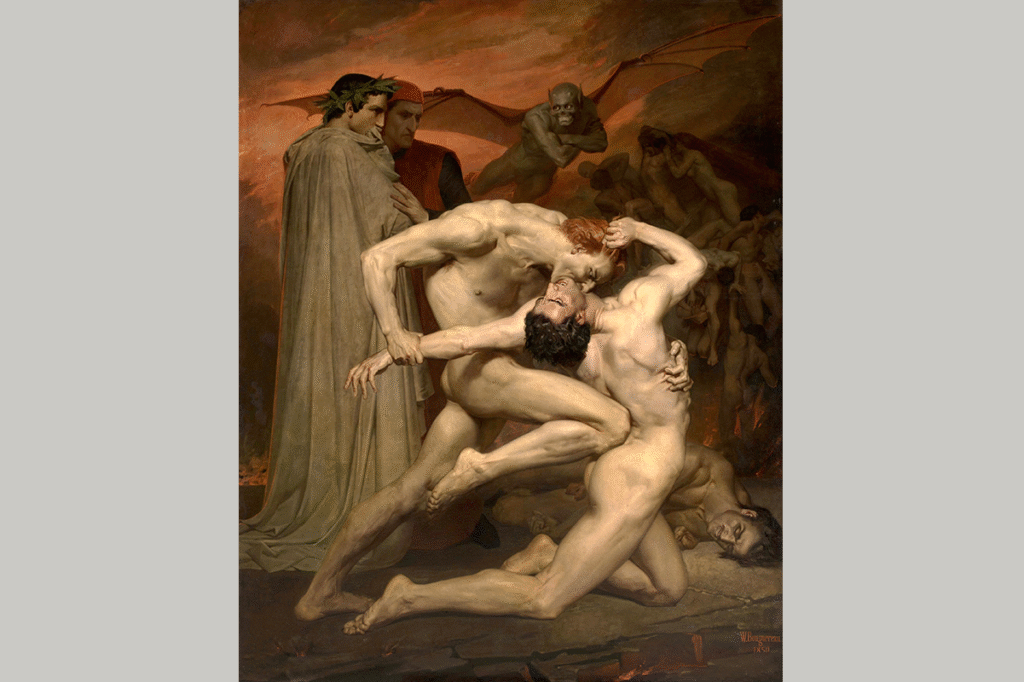

In this essay, I seek to compare Hans Zimmer’s Life Must Have Its Mysteries, composed and published in 2016 for the film Inferno, and William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s Dante and Virgil in Hell, painted in 1850. As a matter of fact, both this painting and this cinematography film music are two different artistic fields that have been separated for more than a century.

Firstly, Bouguereau’s painting is an Academician’s work of Romanticism with Neoclassical influences. In this masterpiece, Bouguereau depicts Dante and Virgil in the eighth circle of Hell, witnessing a grotesque struggle between two damned souls. The composition of this oil on canvas is, in a certain way, overwhelming. The two mannerist figures are twisting in agony, illuminated against the horrific and infernal background. The color palette consists of red, ochres, and shadows that reinforce the chaos and torment of sinners in the netherworld. On the one hand, Dante, awestruck by the scene, tries to find refuge in his mentor, Virgil, also known as The Divine Mantuan. On the other hand, Virgil has his gaze fixed on the horizon, knowing that he has to lead Dante to Beatrice.

According to the Divine Comedy, the eighth circle, also known as the Malebolge, is the realm where the fraudulent, malicious, flatterers, simoniacs, sorcerers, barrators, hypocrites, thieves, sowers of discord, falsifiers, and imposters suffered. The Malebolge has ten bolgias (trenches or ditches). In this painting, Bouguereau is focused on the last bolgia, where Capocchio – an alchemist who was burned as a heretic – is attacked by Gianni Schicchi, a scammer who stole an entire inheritance from a famous and wealthy citizen in Florence (2).

Secondly, Hans Zimmer’s Life Must Have Its Mysteries is the closing piece of Inferno, an American movie released in 2016. The storyline of this film dramatizes Dr. Robert Langdon, who wakes up in a Florence hospital with amnesia and a horrifying vision after helping the Holy See survive an antimatter crisis, and Dr. Sienna Brooks assists him. Together, they follow the trail left by Zobrist, a radical scientist obsessed with Dante, to eliminate a biological terrorist threat called Inferno. Little by little, Brooks and Langdon uncover hidden clues in Florence, Venice, and Istanbul. Brooks betrays Langdon to ensure its release as soon as they find Inferno (the virus created by Zobrtor to reduce the population).

Nevertheless, Langdon and Dr. Elizabeth Sinskey successfully secure the virus in a dramatic climax. The movie ends with Langdon secretly returning the stolen Dante death mask in the Palazzo Vecchio and having an encounter at Harvard University with his friend Dr. Sinskey. She gives him the most precious thing Robert Langdon has: his Mickey Mouse watch.

Hans Florian Zimmer (1957 – ) is one of the most acclaimed film composers of the modern era. He was born in Frankfurt, Germany. He became famous because of this innovative blending of electronic music with orchestral compositions. Some of his masterpieces include Gladiator (2000); Pirates of the Caribbean (2003); Inception (2010); and The Dark Knight (2008). Zimmer has the unique ability to create music scores that accompany films, having a tremendous and unique emotional core.

In Inferno, Zimmer’s piece Life Must Have Its Mysteries is played during the closing scene, where Langdon finds peace back at Harvard University with his friend, Dr. Sinskey, while the stolen Dante death mask has been returned to its place. The music uses a minor key and slow tempo, using an arpeggio for the keyboard and tympani that begins piano but becomes in a crescendo. This gives the scene a sense of mystery but, at the same time, a feeling of peace. Gradually, string arrangements are introduced by a violin and cello solo to finish with choral voices, which are wordless. Unlike his more bombastic works, Life Must Have Its Mysteries is introspective. However, at the same time, all its complexity unfolds gradually. This piece could be considered minimalistic because of the constant repetition of four chords during the whole musical work, altering different instruments and octaves in the melody.

Nevertheless, until this point, the question that may arise in the reader’s mind is this: What is the connection between Hans Zimmer’s Life Must Have Its Mysteries and William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s Dante and Virgil in Hell? Firstly, both masterpieces tell a story. Bouguereau’s Virgil and Dante in Hell narrates the epic journey of the Sommo Poeta and the Divine Mantuan until Dante encounters Beatrice; whereas Life Must Have Its Mysteries could be considered a composition for programmatic music, where Zimmer tells the story of the epic journey of Dr. Langdon, that is to find his way back to Harvard and to encounter his beloved friend Elizabeth Sinskey. Indeed, besides the action and fantasy, the movie tries to be a parallel version of the Divine Comedy.

In Bouguereau’s painting, Dante hugs Virgil because of the scene before him. Nevertheless, with firm security, Virgil has his gaze fixed on the horizon, showing Dante the mysterious and exhausting path he must walk to get to Beatrice and enter Paradise. In this way, the Sommo Poeta wisely says, “Tu sei il mio maestro, lo mio autore; tu sei solo cui io tolsi, lo bello stile che mi ha fatto onore”(3). The same is true in Zimmer’s musical work. The composition’s introduction embodies that mysterious and terrifying scene depicted in Bouguereau’s painting. However, the violin, representing Virgil and Beatrice simultaneously, is the instrument that leads the cello, symbolizing Dante, to that final resolution; proving that the journey through the netherworld is just the beginning of that encounter between Dante, Beatrice, and God.

Foot notes

- D. Alighieri, Inferno (Canto I) lines 1 – 4, Penguin Books Classics Publishers, England, 1949, p. 71.

- Ibid., p. 73. (Thou art my master, and my author thou/ From thee alone I learned the singing strain/ The noble style, that does me honour now). Inferno (Canto I), lines 85 – 87.

Bibliography

- D. Alighieri, The Divine Comedy: Inferno, Penguin Books Classics Publishers, England, 1949

- H.F. Zimmer, Inferno Soundtrack: Life Must Have Its Mysteries, United States, Contemporary Film Music, 2016.

- W. A. Bouguereau, Dante and Virgil in Hell, Oil on Canvas, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France, Academician Romantic Painting, 1850.