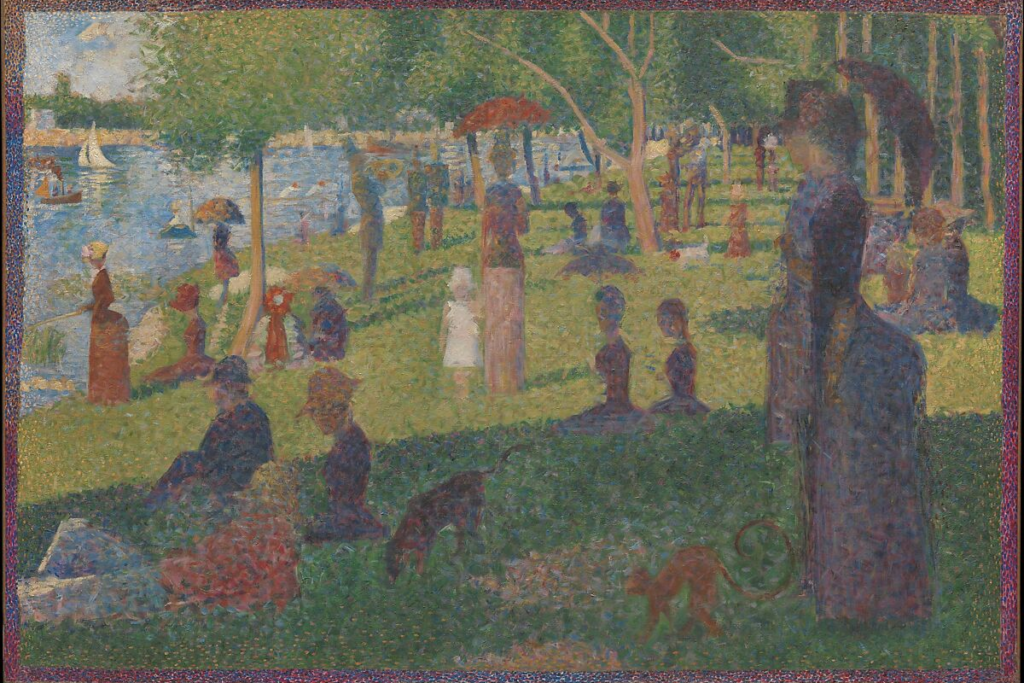

Georges Seurat, Study for “A Sunday on La Grande Jatte” c. 1884, Oil on canvas, 27 3/4 x 41 in. (70.5 x 104.1 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art

The paintings of George Seurat have accompanied me in various ways during my life. In kindergarten, for example, one of the first artworks I remember seeing in an art history book was A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, by Seurat (now at the Art Institute of Chicago). For years, I didn’t remember the name of the painting or its author, but I continued to be impressed by how such a beautiful scene could be constructed with small dots. In high school, I learned that the technique was called pointillism, and I was impressed by Seurat’s interest in optics. Finally, after so many years, when I went to the MET last February 25th, as soon as I saw the painting in The Nineteenth-Century European Paintings and Sculpture Galleries, I had the chance to stop and look at it in person. It is the last study Seurat painted before the final work, now in Chicago.

The paintings of George Seurat have accompanied me in various ways during my life. In kindergarten, for example, one of the first artworks I remember seeing in an art history book was A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, by Seurat (now at the Art Institute of Chicago). For years, I didn’t remember the name of the painting or its author, but I continued to be impressed by how such a beautiful scene could be constructed with small dots. In high school, I learned that the technique was called pointillism, and I was impressed by Seurat’s interest in optics. Finally, after so many years, when I went to the MET last February 25th, as soon as I saw the painting in The Nineteenth-Century European Paintings and Sculpture Galleries, I had the chance to stop and look at it in person. It is the last study Seurat painted before the final work, now in Chicago.

The subject of the painting is typical of the period: a group of Parisians enjoying the day on the banks of the Siena River: «The visitors, Seurat’s “modern people”, are taking a genteel stroll or relaxing in the shade. No one is bathing, no one has removed their clothing»[1]. Undoubtedly, what captivates our attention is the novelty of the technique; of pointillism. In fact, in the Museum, I saw the painting differently from the angle from which I first observed it: first, the farther away, the more precise it appeared, while second, when approaching towards it, the dots appear more clearly, and the image becomes less sharp.

Seurat’s work is based on a deep investigation of color theory: «he had learned that colors reach the eye in the form of light of varying wavelengths, and are only mixed once they get there»[2]. After his studies, instead of mixing pigments on the palette, he applied dots to the canvas. As one of the brothers said to me while viewing the work in the Museum: it is as if we were in front of one of the old color televisions, in which the colored pixels are observed when you zoom in, but when you zoom out, they give rise to the image before our eyes.

Seeing the painting in person at the MET helped me experience the power of pointillism and the relationship between science and art that many Impressionists applied in their work. The 19th century was a century of increasing interest in science and technology, and Seurat is an excellent example of this relationship. In the context of my humanistic studies and religious formation, this painting can be an example of the bridge we, as Legionaries, can build between culture and faith. Seurat made with pointillism a new bridge between science and art; by appreciating the beauty of his work and rediscovering the science behind it, we can also help people rediscover the value of faith in art; the foundation of all beauty which is God himself.

[1] R.M. HAGEN, R. HAGEN, What Paintings Say. 100 Masterpieces in Detail, Taschen, Cologne 2016, p. 684.

[2] Ibid., p. 687.