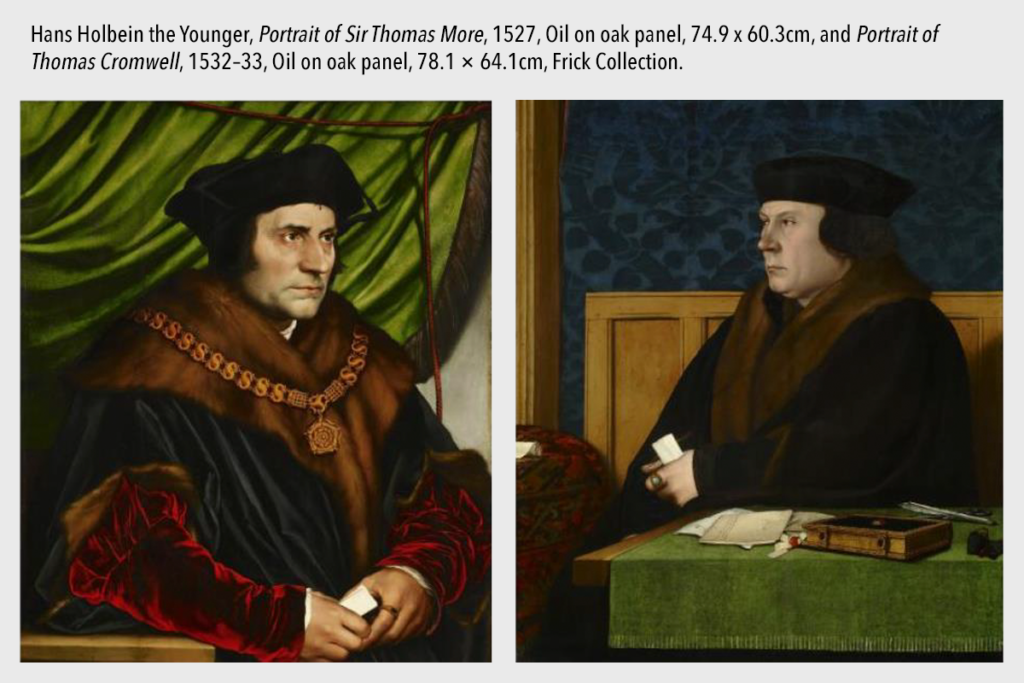

Portrait of Sir Thomas More and Portrait of Thomas Cromwell, by Hans Holbein the Younger at the Frick Collection, New York

Visiting the Frick Collection on November 12 had a peculiarity: the art pieces were not on display in the Frick Mansion, which is temporarily closed for restoration. In their new temporary location, there were two artworks that captivated my attention because of how they were exhibited: the Portrait of Sir Thomas More and the Portrait of Thomas Cromwell, both by Hans Holbein the Younger. Is this placement in the gallery due to the new temporary location? Looking at photos of their location in the Frick Mansion, I see that they are placed similarly on the same wall, and the same effect is generated: the contrast between two crucial and opposite characters of the Anglican Reformation.

Both portraits are made with the same technique: oil on oak panel. In addition, there is only a five-year difference between one painting and the other. However, between the two artworks and how the Frick Collection exhibits them, it is easy to recognize some differences.

Saint Thomas More looks to the right while Cromwell faces the left. “Holbein presents More robed in rich velvet and fur, with a gold chain of office displaying his status and service to the king.”1 His face, although serious, reflects serenity. The portrait was painted in 1527. In 1529, he was appointed Lord Chancellor, but a year later, he wouldn’t sign the letter asking the Pope to annul the King’s marriage. Then, he would resign his office, and refusing to refute the authority of the Pope, he was condemned to death less than a decade after his friend, Hans Holbein, painted this artwork.

Nevertheless, the portrait reflects the personality of the saint very well. Despite his rich vestments and chain of service to the King, his firm and serene gaze simultaneously demonstrates the certainty of his conscience, to which he will remain faithful until martyrdom. It is as if he knows that difficult times are approaching, and he has no time to distract himself with banalities. He will be stripped of his earthly riches to remain faithful to God, rather than the King. But he does not lose his peace; his trust is in God.

On the other hand, looking at Cromwell’s face, we see a severe man with an attitude opposite to that of More’s. The frown is furrowed, and the lips and gaze reflect an attitude of arrogance and anger. Unlike More, only one of his hands is visible, in which his ring is reflected. The other hand is hidden under the table as if clinging to his ideas. Indeed, Cromwell was a leading figure in the Anglican reform, promoting the divorce of the King and Catherine of Aragon and opposing papal authority.

The discrepancy between the two portraits leads me to contemplate the opposing attitudes of saint and sinner. In the end, both characters are condemned to death, but the attitude with which they approach the end of their lives is entirely different. The paintings and the way they are displayed in the Frick Collection invite me to follow the example of St. Thomas More, to know how to divest myself of the dignities of this world and, in fidelity to my conscience, to serve God with serenity. Both artworks and their comparison can be helpful for the apostolate with lay people, especially those involved in the world of politics, where they are called, like More, to be light in the midst of darkness.

1 S. HODGE, Art in Detail, 100 masterpieces, Thames & Hudson, London 2016, p. 88.