I chose Allegri’s Miserere and Titian’s Christ and the Good Thief for this comparative essay. The Miserere was composed by Gregorio Allegri for the Holy Week Offices to be sung in the Sistine Chapel of the Vatican under the reign of Urban VIII, circa 1638. The text is from Psalm 50 (51), the Miserere.

I chose Allegri’s Miserere and Titian’s Christ and the Good Thief for this comparative essay. The Miserere was composed by Gregorio Allegri for the Holy Week Offices to be sung in the Sistine Chapel of the Vatican under the reign of Urban VIII, circa 1638. The text is from Psalm 50 (51), the Miserere.

I first heard this musical setting more than ten years ago, in my adolescence. Before I heard it, my singing teacher asked me to pay special attention to the boy soprano’s white voice in the highest tones. Even though I had no excellent knowledge of Latin then, I was impressed as I could perceive the beauty of God’s Mercy; the cry of the soul to the Savior asking for salvation. For me, this is not a cry of despair but rather of trust, love, a sigh of surrender.

This confidence is expressed through the high tone of the boy soprano’s voice in parts of the psalm that are essential to this cry of trust. For me, these parts are: “munda me,” “manifestasti mihi,” “visceribus mei”, “iustitia tuam” and the “muri Ierusalem” at the end. It is as if the effect of God’s mercy on the soul is expressed with the beauty of music: God purifies, erases iniquities, and, finally, allows us to enter the walls of the new heavenly Jerusalem. The music is also ordered in such a way that it expresses the process of mercy; and that is why the first time I listened to it, even without understanding the lyrics entirely, my soul was moved toward contemplating God’s mercy and compassion.

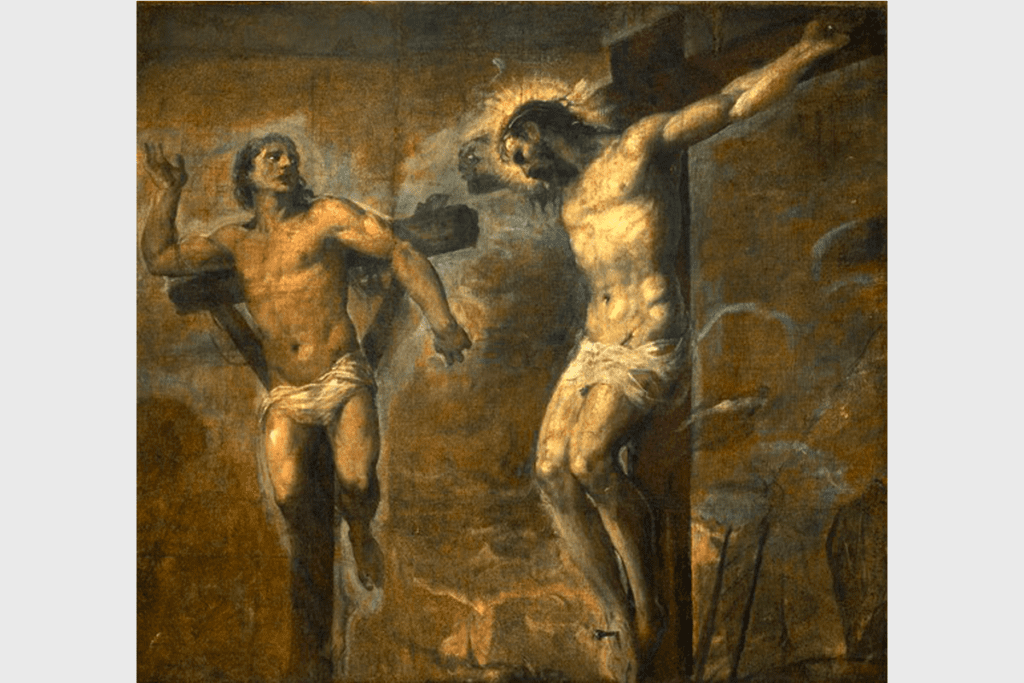

I want to compare this musical work with the painting Christ and the Good Thief, circa 1566, by Titian. Between Allegri’s Miserere and this painting, there is only a 70-year gap. Both works express well the cultural atmosphere of the time, which also influenced the arts, as well as the piety and religious experience of the faithful.

Looking at the face of the good thief in the painting, I experience the same feelings as when I am listening to the Miserere. His gaze is directed towards Christ; his hand towards heaven. He acknowledges his fault, as the words of the psalm say, and Christ bows his head towards him as a sign that he grants forgiveness. I can also perceive in this painting a dialogue between the soul and God, which is the cry of hope asking for divine mercy in the Miserere.

The words that resonated most with me from the Miserere, and that I noted above (“munda me,” “manifestasti mihi,” “visceribus mei,” “iustitia tuam” and “muri Ierusalem”), are also reflected in the painting. This makes visually explicit the process of divine forgiveness: the thief acknowledges his guilt; he hopes to be purified; he is exposed before Christ on the Cross without a mask or any lies, and Christ in turn bends down to infuse the peace of His Spirit into his entrails. In acknowledging his guilt, the thief proclaims the divine justice that has set him free, concluding with Jesus’ promise: today, you will be with me in the new Jerusalem.

We are all wounded by original sin, experience concupiscence, and suffer the consequences of our sins, but we are consoled by the mercy of the God who has become flesh in order to rescue us and invite us to Heaven. In short, both Allegri’s Miserere and Titian’s painting reflect the experience of my soul, which has encountered divine mercy and cries out for it with confidence and hope, knowing that Love purifies, renews, and saves.